The “Habsburg Jaw” was more than a family trait—it was the visible result of centuries of dynastic inbreeding. From Charles V to Charles II, the dynasty’s pursuit of purity left a lasting mark on both faces and history.

A Face That Told a Dynasty’s Story

A long chin, a drooping lip, a face that painters could not ignore.

For centuries, the portraits of Europe’s most powerful royal family carried the same unmistakable mark: the Habsburg Jaw.

This was not a mere family resemblance. It was the visible cost of centuries of inbreeding—an attempt to preserve dynastic power that ultimately helped bring the Spanish Habsburgs to an end.

What Was the Habsburg Jaw?

Modern medicine calls it mandibular prognathism: the lower jaw grows too far forward, disrupting the bite and reshaping the face.

Contemporaries noticed it as much as modern historians do. Ambassadors and courtiers described monarchs who spoke poorly, drooled constantly, or struggled to eat. In its most severe form, the condition was tied to infertility and developmental disorders.

Why Did It Appear?

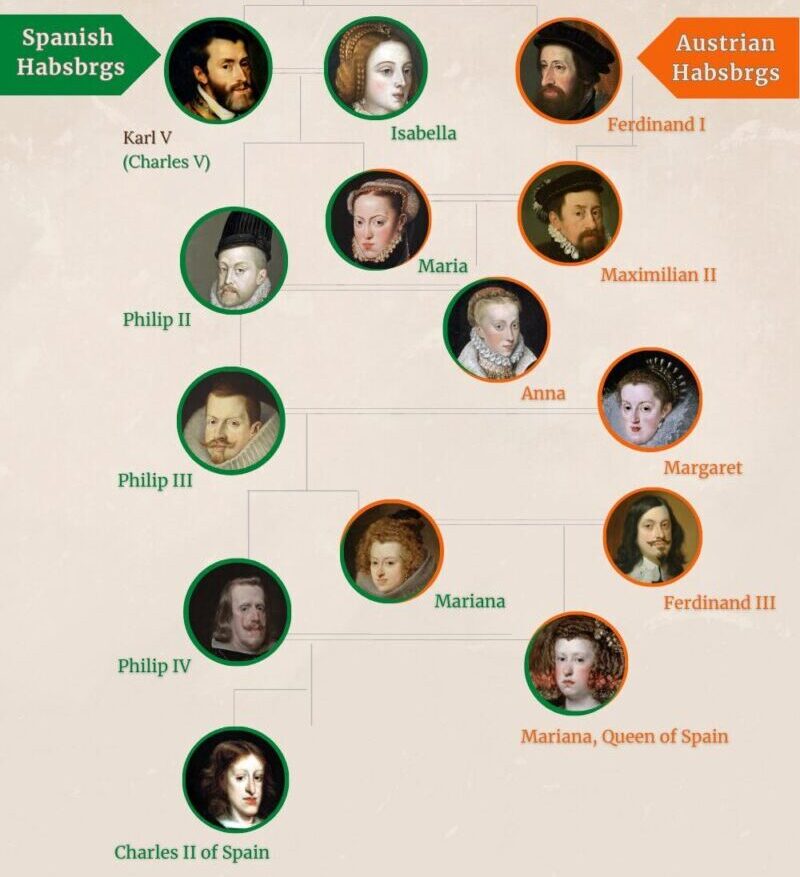

Family tree of the Spanish Habsburgs: created by Habsburg Hyakka. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

The answer lies in dynastic marriage politics.

The Habsburgs saw themselves as defenders of a “pure” bloodline. They rejected alliances with Protestant or “lesser” houses, leaving only close relatives as acceptable spouses.

- Philip II married his niece, Anna of Austria.

- Philip III married his cousin, Margaret of Austria.

- Philip IV remarried his niece, Mariana of Austria.

Each generation narrowed the genetic pool further. What seemed like a strategy to protect the dynasty’s prestige instead magnified hereditary defects.

Faces of Decline

Portraits show how the condition deepened:

- Charles V (1500–1558) already displayed a protruding chin.

Karl V (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

-

Philip IV (1605–1665) appears with a long face and heavy lower jaw in Velázquez’s paintings.

Philip IV of Spain (Source: Wikimedia Commons,Public Domain)

- Charles II (1661–1700), the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, suffered the most. His parents were uncle and niece, giving him an inbreeding coefficient of 0.254—four times that of a cousin marriage.

Reports describe him as frail, infertile, and intellectually disabled. His reign ended without an heir, plunging Spain into the War of the Spanish Succession.

Spain’s Twilight

Charles II’s physical decline mirrored Spain’s political fall.

- Silver from the Americas was dwindling.

- Portugal and the Netherlands had broken away.

-

Endless wars left the treasury bankrupt.

At court, priests and astrologers tried to heal the king while foreign powers prepared to divide his empire. When Charles II died in 1700, the Spanish crown passed to the French Bourbons, closing the chapter on two centuries of Habsburg rule in Spain.

Science Confirms the Pattern

In 2009, a study by Gonzalo Álvarez and colleagues analyzed Habsburg genealogies and portraits. They found a clear correlation: the higher the inbreeding coefficient, the more pronounced the Habsburg Jaw.

The dynasty’s most famous feature was no accident. It was the direct result of marriage policies designed to preserve power.

Beyond Spain

AI generated image

The condition did not vanish with Charles II. Austrian Habsburgs like Leopold I showed similar traits, and even Marie Antoinette’s portraits reveal a faint trace of the elongated chin.

The “family look” never again reached the extremes of Spain’s last king, but it lingered—a reminder that dynastic choices carried consequences across generations.

A Dynasty Undone by Its Own Blood

The Habsburg Jaw is more than a medical curiosity. It is the physical trace of a dynasty that tried to control its fate through blood—and in doing so, sealed its decline.

The portraits remain, silent witnesses to a royal house undone by its own design.

References

-

Álvarez, G., Ceballos, F. C., & Quinteiro, C. (2009). The role of inbreeding in the extinction of a European royal dynasty. PLoS ONE, 4(4): e5174.

-

Archivo General de Simancas (Spanish Royal Archives)

-

Biblioteca Nacional de España (National Library of Spain)

-

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library, Digital Collections)

-

Portraits: Jacob Seisenegger, Diego Velázquez, Juan Carreño de Miranda (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

※ Images labeled “AI generated image” are AI-created illustrations and not historical artworks.